The Grande Trump Strategy: Manufacturing Chaos, Refinancing Debt, and Rewriting Trade Logic

The Trump administration’s April 2nd tariff announcement was bound to make headlines, but not for the reasons you might expect. Rather than introducing reciprocal tariffs, that is, matching the tariffs U.S. trading partners impose on American goods, the administration chose a different, more theatrical path.

Standing in the Rose Garden, Trump declared:

“The nations that treat us badly, we will calculate the combined rate of all their tariffs, non-monetary barriers, and other forms of cheating”

To drive the point home, he hoisted a large board listing supposed tariff rates charged on U.S. goods. But almost immediately, analysts noticed something was off. The numbers didn’t line up with actual trade data, and then came the reveal of the formula behind the claims: a baffling ratio of the U.S. trade deficit with a country to the value of imports from that country.

In this logic, if the U.S. imports $100 billion from a country and exports $50 billion, that’s seen as a 50% effective tariff being charged on the U.S by the trading partner. This is, of course, not what a tariff is.

Effectively, the administration treated trade deficits-when the U.S. buys more from a country than it sells-as proof of that country “cheating.” The solution? Slap on retaliatory tariffs calculated from this crude metric.

For the 115 countries with which the U.S. runs a trade surplus that is, by Trump’s logic, the ones the U.S. is “cheating”, the administration appeared to simply assume they imposed a 10% tariff on U.S. exports regardless of whether the country actually has trade restrictions against the U.S. In turn, the Trump administration imposed a blanket 10% “retaliatory” tariff.

The Debt Refinance Motive

Now let’s zoom out.

The U.S. government debt stands at $36 trillion, with over 11% of annual budget spending going to debt servicing. The annual deficit-the excess of spending over revenue-currently sits above $1.1 trillion. Enter a speculated three-pronged strategy for financial redress:

Tariffs to raise revenue.

Tax cuts to cushion impact of tariffs on American households.

DOGE to cut government spending by $4 billion per day.

Following the stock market sell-off triggered by the tariff announcement, supporters suggested a fourth strategy intentionally masterminded by the administration, the refinancing motive.

Over the remainder of 2025, nearly $9 trillion of U.S. government debt will mature and need refinancing at prevailing market rates. The tariff-driven uncertainty has already rattled consumers and businesses, dampening confidence and pushing bond yields down.

Lower yields mean cheaper borrowing. Making simple assumptions about how long yields stay suppressed, the U.S. could refinance its debt at lower costs, saving up to $500 billion over the next decade, or $50 billion per year.

To recap: through the chaos of Phase 1 of this “grande strategy,” the government engineered market fear that wiped out over $10 trillion in private wealth via falling equity markets dealing heavy blows to retirement accounts, to save itself an estimated $50 billion a year in interest payments.

Balancing the Numbers

The stock market will eventually recover and make up its losses-hopefully in short order. But uncertainty doesn’t just affect the stock market. It stalls the real economy.

Businesses delay expansions. Mergers and acquisitions are postponed. Households pull back on major purchases. Essentially, the private sector is paralyzed while the public sector tries to balance its books through what supporters insist is engineered chaos.

Looking at the other tools in the Trump playbook, let’s consider the best-case scenario:

DOGE delivers $4B in daily spending cuts, or $1 trillion by year-end

Tariffs raise $620 billion in the first year and $5.5 trillion over a decade (per Capital Economics)

TCJA-style tax cuts return, offering modest personal savings but costing the government $4 trillion over ten years

Even in this optimistic projection, and ignoring the possibility that DOGE’s indiscriminate cuts reduce government efficiency or revenue collection, the revenue and cost savings would only partially offset the economic slowdown and tax cut costs.

The reckless implementation of tariffs, eerily reminiscent of DOGE’s haphazard cuts, creates a high-stakes gamble with limited room for error.

All Those Great Manufacturing Jobs

Manufacturing has long been at the heart of U.S. economic nostalgia. But the numbers tell a different story.

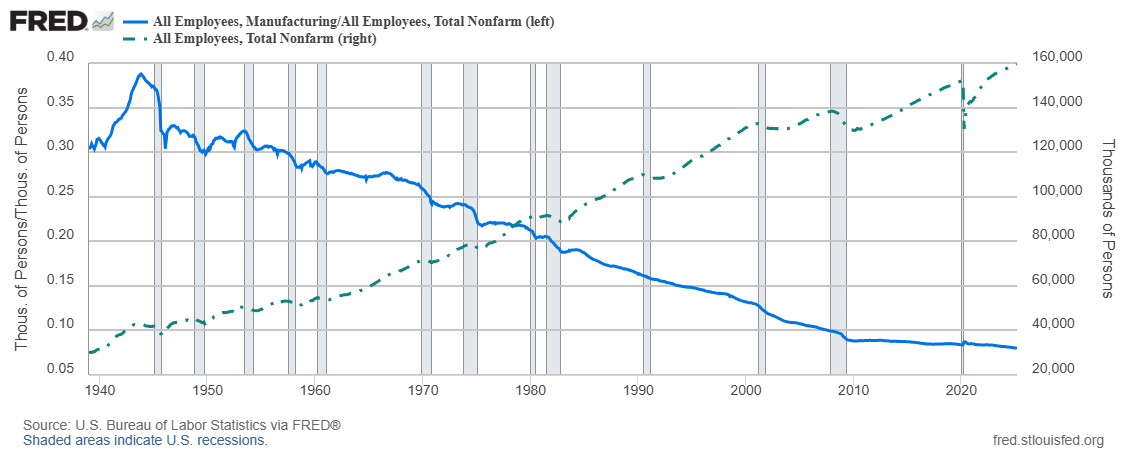

Since its peak in 1979 with 19.5 million workers, U.S. manufacturing employment has dropped to under 13 million. Germany has seen similar declines. As other sectors expanded, U.S. manufacturing stagnated and began its long, steady decline in the late 2000s.

Despite the rhetoric of a manufacturing renaissance, the U.S. is currently at or near full employment. Immigration restrictions have shrunk the labor pool. American manufacturers are already struggling to find workers.

So who’s going to do these jobs?

If the Trump administration is serious about restoring manufacturing, it faces labor shortages, mismatched skills, and the need for massive financial incentives and retraining of workers.

Assuming the promise to bring back manufacturing jobs is genuine-despite there already being so many manufacturing jobs that nobody wants-, perhaps the plan is to absorb and retrain laid-off federal workers from DOGE cuts to fill manufacturing roles. The catch? That’ll take years. So will building new factories.

Meanwhile, uncertainty created by the administration’s erratic policymaking may delay investment in U.S. manufacturing, as businesses try to interpret government intentions.

In the meantime, tariffs will drive up the cost of raw materials and intermediate goods, causing the price of products manufactured in the U.S. to soar. Add in labor shortages and increased domestic demand due to import substitution, and the result is sharply higher prices for American households, whether you buy American or foreign.

Who Pays?

The rich may cut back on discretionary spending. The poor—who spend most of their income on essentials—will feel the squeeze. Ironically, the working class, whom these tariffs aim to protect, may end up paying the most.

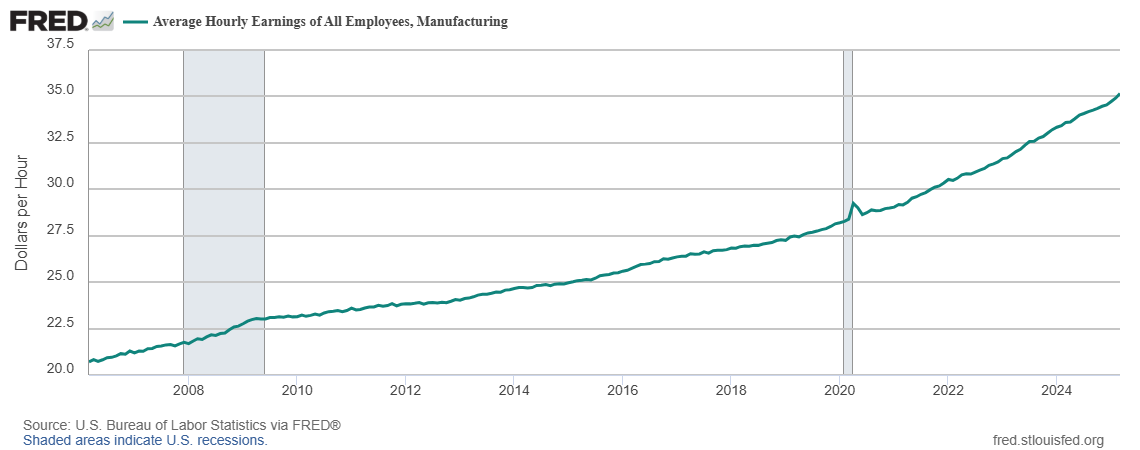

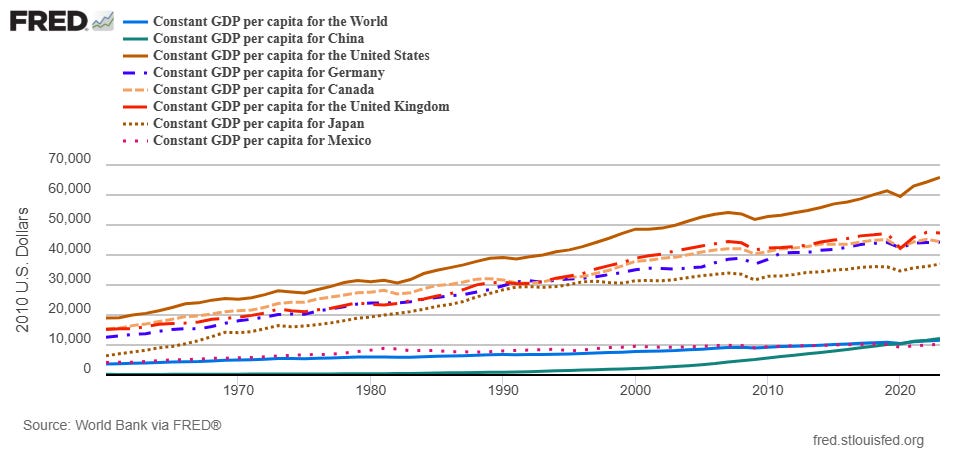

If tariffs persist and manufacturers do bring production back, they’ll do so at a steep cost. A product made by a $68,000-a-year U.S. worker can’t compete price-wise with one made for $15,000 in Mexico or $10,000 in China. Consumers won’t be paying for better quality, they will be paying to subsidize inefficiency.

Reduced imports due to tariffs would also mean reduced demand for foreign currencies and a stronger USD. Making already expensive U.S. manufactured products even more expensive abroad, hurting American exports and increasing U.S. trade deficits. In other words, the exact opposite of what the Trump administration is aiming for.

It’s likely that companies opening U.S. factories will reserve those facilities to serve the U.S. and a few wealthy markets, while maintaining cheaper production hubs abroad for everyone else.

The result? A check on U.S. consumerism and, potentially, a significant drag on growth. And since consumer spending is the main driver of U.S. GDP, this could ripple across the economy.

Ultimately, the Trump administration’s attempt to redistribute wealth from the poorer countries it trades with to itself will likely leave everyone worse off.

Globally, decreased U.S. demand for foreign goods could tip trading partners into a recession, which will feed back into lower demand for U.S. made products. Domestically, Americans may cut back on spending altogether, limiting gains from reshoring.

Final Thoughts

In many ways, this is a grand experiment. The U.S. is supposedly using policy-induced uncertainty to refinance its debt at cheaper interest rates, it is funding tax cuts with tariff revenues, and attempting a manufacturing comeback, all while rattling global trade norms.

Will it work? Will it implode? One thing’s certain, there’s no clear winner yet.

But perhaps you see one. Drop your thoughts below.