The Future Belongs to The Enterprising

The first of a few, interrogating the motives behind the artificial intelligence drive

Some years ago as a young undergraduate student, I sat in class and listened to a professor describe a future where all jobs are automated and humans spend their time in leisure. I don’t remember much else from that lecture, except how incredulous that future seemed to me, and how dull I thought it would be to live a life solely devoted to leisure.

Fast forward to 2025, and AI thought leaders now warn that that future is less than 5 years away, each offering their view of what the future looks like, ranging from optimistic to existential.

Bill Gates on The Tonight Show, predicted that only three jobs will survive the AI wave: coders, energy specialists, and biologists.

Given the primary objective to maximize profit in a capitalist system, there is no doubt that corporate leaders will slash costs the moment reliable AI alternatives become available, potentially leading to job losses on a scale we haven’t seen before.

Automation itself isn’t new. Over the past century, we’ve seen farms mechanized, factories automated, and banks digitized. What’s different now is speed and scope. This time, the displacement won’t be gradual or industry-by-industry. It could be sudden, sweeping across white-collar and service jobs alike.

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, a leading AI research company predicts that U.S. unemployment will rise to 20 per cent (up from 4.2 per cent), with significant job losses in tech, finance, and law, and 50 per cent of entry level jobs wiped out.

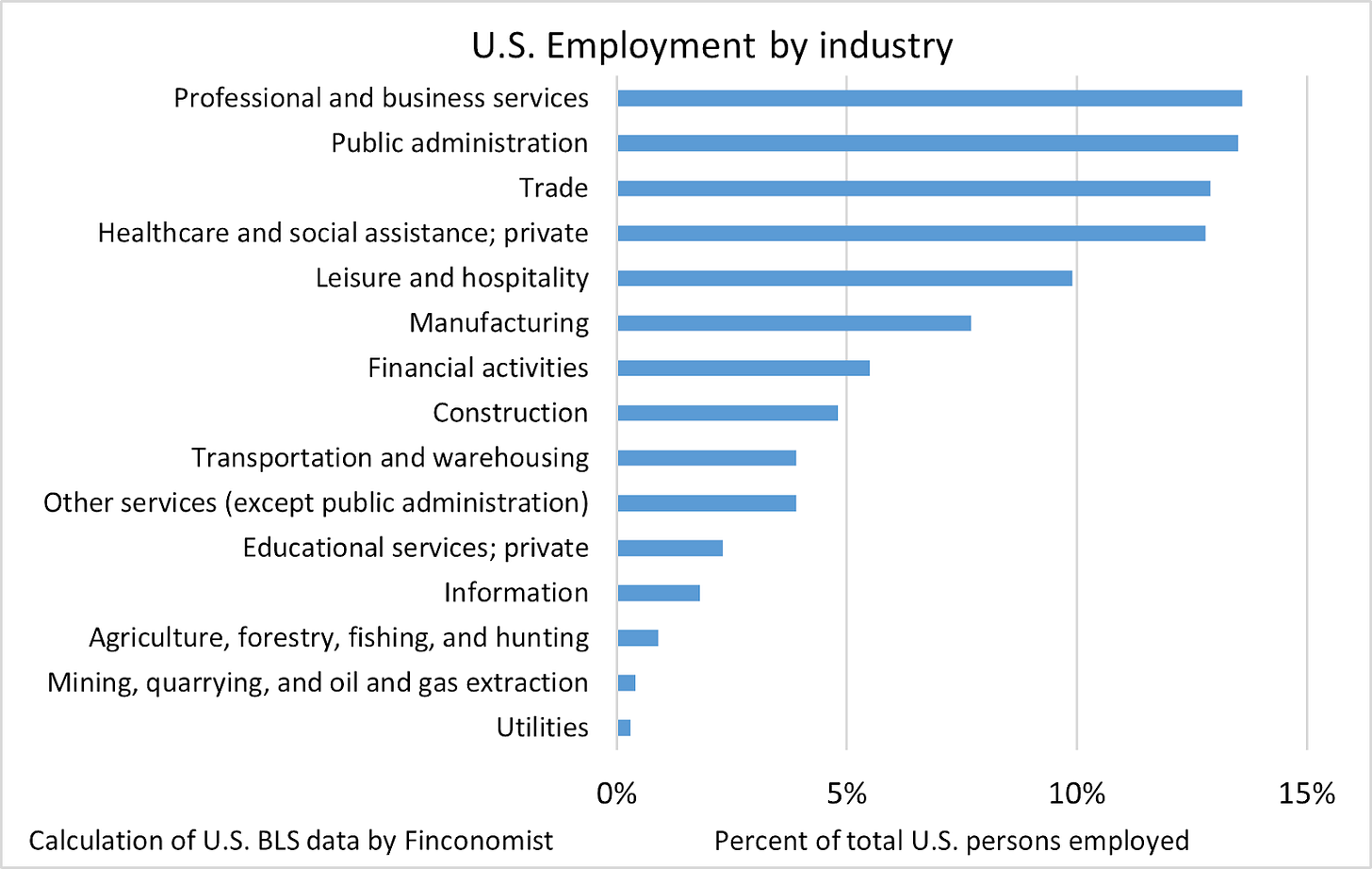

In countries like the U.S. and Canada where just over 80 per cent of jobs are in services, the proliferation of AI agents capable of carrying out repetitive and analytical tasks means that a large percentage of these jobs can be replaced within the next few years.

A 20% loss in service jobs alone in the U.S. will add about 27.5 million more unemployed people to the current unemployed count of 7.2 million. In Canada, a 20% loss in service jobs would push unemployment from 1.5 million to roughly 4.5 million people, a threefold increase.

Not even jobs in the goods producing sectors are safe, with advancements in robotics trailing not too far behind AI. Elon Musk predicts that robots will be in homes within the next five years, making their arrival in factories equally imminent.

The Capitalist’s Utopia

OpenAI’s Sam Altman paints an optimistic picture of a world where work is optional. Altman, in a 2021 post that reads like a manifesto for the future he is now designing, wrote:

"This revolution will generate enough wealth for everyone to have what they need, if we as a society manage it responsibly."

That is a big “if”. This vision calls for an outsized role for governments and demands massive innovation, coordination, and consensus, particularly around the necessary redistribution of wealth. Altman speaks of AI doctors and AI teachers in this fanciful future where wealth is redistributed through shares in AI companies making everyone equity owners in this nouveau capitalist design.

While futurists laud the liberation of workers, it is also the case that capitalism is being liberated from workers, given the human propensity to get hurt, needing time to heal, vacation days, and asking for pay raises. But what does this “liberation” mean for the majority?

There are other ways this could go…

Altman predicts that Americans could receive an annual allocation of $13,500, which will supposedly be enough to have all they need in a low cost AI economy with no jobs. Bill Gates predicts humans will no longer be needed for most things, with advanced AI capable of everything from folding laundry to writing novels.

Yet a more hopeful path exists. One where AI is used to augment human productivity and ingenuity, not to replace it. It is inevitable that certain jobs will cease to exist while others are radically transformed.

But a complete takeover that makes humans surplus to requirements deserves serious scrutiny. Especially when the majority are expected to be content living on $13,500 a year, fending off existential dread while struggling to find purpose in a world with shrinking opportunities and a growing loss of control over their own futures.

But even if we are headed towards a society that depends on a universal basic income, the active participation of democratically elected governments in designing that future is paramount. This allows for social impact consideration and designing a UBI system that caters to the majority.

The transition is the danger zone

Regardless of what future lies ahead, it is reasonable to expect job displacements over the next few years.

Yes, AI could bring significant benefits: productivity gains, lower costs, even new industries. But governments appear woefully unprepared for the pace and scale of disruption. Meeting this challenge may require rethinking employment insurance, designing fiscal tools to absorb economic shocks, and investing in large-scale, effective retraining programs. Without proper planning, governments risk mass social unrest.

On the individual level, it is evident that only the enterprising will thrive if the scale of disruption is as bad as is being predicted.

The brutal truth is, most people are not naturally entrepreneurial. In the U.S., just under 6% of workers are self-employed; in Canada, 13%. Even with drive and skill, finding new work will be hard if millions are competing for the same limited opportunities.

Hedge fund manager Ray Dalio who has been sounding the alarm suggested AI could wipe out 40% of jobs. If four in ten people are unemployed, “pivoting” into enterprise becomes that much more difficult.

Still, the rise in side hustles over recent years may offer some hope. According to recent surveys results, over 50 per cent of Canadians & 27 per cent of Americans reported having a side hustle, a trend that could help individuals adapt to a rapidly changing job market.

So far, changes to the workforce are occurring in little pockets, with jobs disappearing as a result of AI. Klarna CEO reported reducing the company’s headcount by almost 40 per cent, from about 5,000 workers to 3,000 workers due in part to their adoption of AI tools.

Fortunately, there are no definitive signs that AI is displacing workers at scale as yet. Although, early signs may be clouded by increased global economic uncertainty and already soft labor markets across most G7 countries.

Final word

There is a possibility that AI simply gets integrated into our work and lives, a human-centric, trustworthy and responsible AI as was promoted at a global AI safety summit hosted by the UK two years ago.

Whatever the case, governments have a crucial role to play. The future of work leisure is contingent upon the effective redistribution of wealth from the AI economy, to the rest of society.

All things considered, it is clear that the future belongs to the enterprising. The ability to adapt and create value for the owners of capital beyond the capabilities of AI and robots will be highly rewarding for those who succeed.

Meanwhile, for the rest of society, if UBI systems fail, perhaps we see a regression to subsistence living, consisting of small scale farming, odd jobs, and trade by barter.

Ultimately, I believe the most difficult part of this is in the transition period. The period where people may begin to lose their jobs, and employment insurance systems become strained as people struggle to find their footing. In all of this, it is crucial to remain nimble, ready to learn and adapt.